Four days after Russia’s ill-fated Luna-25 moon probe crash landed, India’s heavily instrumented Chandrayaan-3 robotic lander dropped out of orbit for a rocket-powered descent to the lunar surface, successfully touching down near the moon’s south pole.

The automated landing boosted India’s increasingly sophisticated space program to the level of “space superpower,” making it only the fourth nation, after the United States, China and the former Soviet Union, to land an operational spacecraft on the moon and the first to reach the south polar region.

ISRO/Indian Defence Network

Circling the moon in an elliptical orbit with a high point of 83 miles and a low point of just 15.5 miles, Chandrayaan-3’s braking engines fired up around 8:15 a.m. EDT, at an altitude of about 18 miles, to begin the powered descent to the surface.

After dropping to an altitude of about 4.5 miles, and slowing from 3,758 mph to about 800 mph, the spacecraft paused the descent for about 10 seconds to precisely align itself with the targeted landing site.

It then continued the computer-controlled descent to touchdown, beaming back a steady stream of images showing its approach to the lunar surface below. With Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi looking on via a television link, the spacecraft settled to touchdown around 8:33 a.m.

Engineers, mission managers, dignitaries and guests in the Indian Space Research Organization’s control center erupted in cheers and applause.

“We have achieved soft landing on the moon,” said ISRO Chairman Shri Somanath. “Yes, on the moon!”

ISRO webcast

Modi then addressed the ISRO team, speaking in Hindi but adding in English, “India is now on the moon!”

“The success belongs to all of humanity,” he said. “And it will help moon missions by other countries in the future. I’m confident that all countries in the world … can all aspire for the moon and beyond. … The sky is not the limit!”

Chandrayaan-3’s dramatic landing, carried live on YouTube and the Indian space agency’s website, capped a determined four-year effort to recover from a software glitch that caused the Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft to crash moments before touchdown in 2019.

It initially appeared Russia might steal a bit of India’s thunder with the planned landing Monday of the Luna-25 probe, Russia’s first attempt to touch down on the moon in nearly 50 years.

But over the weekend, a thruster firing went awry and Roscosmos, the Russian federal space agency, reported the spacecraft had “ceased to exist” after a “collision with the lunar surface.”

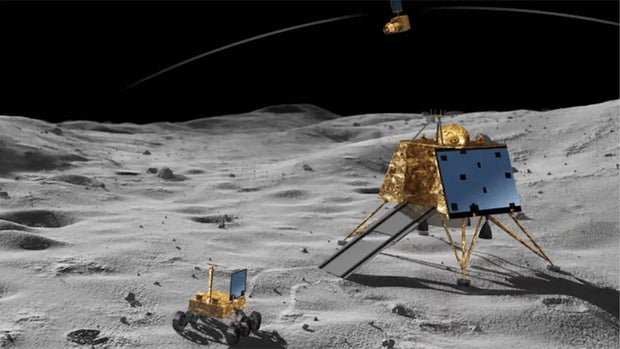

In contrast, Chandrayaan-3’s orbital adjustments went by the book, setting up a touchdown that coincided with lunar dawn at the landing site. Designed to operate for a full two-week lunar “day,” Chandrayaan-3 consists of the solar-powered Vikram lander and an 83-pound six-wheel rover named Pragyan that was carried to the surface nestled inside the lander.

The lander is equipped with instruments to measure temperature and thermal conductivity, seismic activity and the plasma environment. It also carries a NASA laser reflector array to help precisely measure the moon’s distance from Earth.

The rover, which has its own solar array and is designed to roll down a ramp to the surface from its perch inside the lander, also carries instruments, including two spectrometers to help determine the elemental composition of lunar rocks and soil at the landing site.

While science is a major objective, the primary goal of Chandrayaan-3’s mission is to demonstrate soft-landing and rover technology as critical stepping stones to future, more ambitious flights to deep space targets.

“Roscosmos State Corporation congratulates Indian colleagues on the successful landing of the Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft,” the Russian space agency said in a post on Telegram. “Exploration of the moon is important for all mankind, in the future it may become a platform for deep space exploration.”

ISRO

Launched Aug. 14, the mission is the first to reach the moon’s south polar region, an area of heightened interest because of the possibility of accessible ice deposits in permanently shadowed craters. Ice offers a potential in situ source of air, water and even hydrogen rocket fuel for future astronauts.

The possibility of ice deposits has triggered a new space race of sorts. NASA’s Artemis program plans to send astronauts to the south polar region in the next few years and China is working on plans to launch its own astronauts, or “taikonauts,” to the moon’s south pole around the end of the decade.

India is clearly interested, as is Japan, the European Space Agency and several private companies that are building robotic landers of their own under contracts with NASA as part of the agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program.

Credit: Source link