Sergio Ermotti, CEO of Swiss banking giant UBS, during the group’s annual shareholders meeting in Zurich on May 2, 2013.

Fabrice Coffrini | Afp | Getty Images

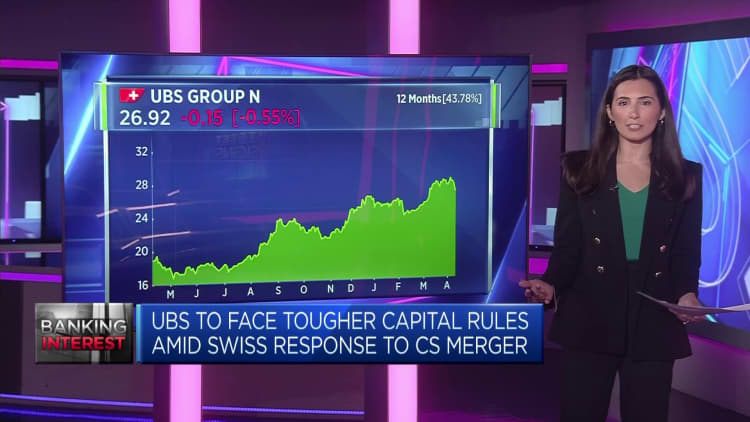

Switzerland’s tough new banking regulations create a “lose-lose situation” for UBS and may limit its potential to challenge Wall Street giants, according to Beat Wittmann, partner at Zurich-based Porta Advisors.

In a 209-page plan published Wednesday, the Swiss government proposed 22 measures aimed at tightening its policing of banks deemed “too big to fail,” a year after authorities were forced to broker the emergency rescue of Credit Suisse by UBS.

The government-backed takeover was the biggest merger of two systemically important banks since the Global Financial Crisis.

At $1.7 trillion, the UBS balance sheet is now double the country’s annual GDP, prompting enhanced scrutiny of the protections surrounding the Swiss banking sector and the broader economy in the wake of the Credit Suisse collapse.

Speaking to CNBC’s “Squawk Box Europe” on Thursday, Wittmann said that the fall of Credit Suisse was “an entirely self-inflicted and predictable failure of government policy, central bank, regulator, and above all [of the] finance minister.”

“Then of course Credit Suisse had a failed, unsustainable business model and an incompetent leadership, and it was all indicated by an ever-falling share price and by the credit spreads throughout [20]22, [which was] completely ignored because there is no institutionalized know-how at the policymaker levels, really, to watch capital markets, which is essential in the case of the banking sector,” he added.

The Wednesday report floated giving additional powers to the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority, applying capital surcharges and fortifying the financial position of subsidiaries — but stopped short of recommending a “blanket increase” in capital requirements.

Wittman suggested the report does nothing to assuage concerns about the ability of politicians and regulators to oversee banks while ensuring their global competitiveness, saying it “creates a lose-lose situation for Switzerland as a financial center and for UBS not to be able to develop its potential.”

He argued that regulatory reform should be prioritized over tightening the screws on the country’s largest banks, if UBS is to capitalize on its newfound scale and finally challenge the likes of Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Citigroup and Morgan Stanley — which have similarly sized balance sheets, but trade at s much higher valuation.

“It comes down to the regulatory level playing field. It’s about competences of course and then about the incentives and the regulatory framework, and the regulatory framework like capital requirements is a global level exercise,” Wittmann said.

“It cannot be that Switzerland or any other jurisdiction is imposing very, very different rules and levels there — that doesn’t make any sense, then you cannot really compete.”

In order for UBS to optimize its potential, Wittmann argued that the Swiss regulatory regime should come into line with that in Frankfurt, London and New York, but said that the Wednesday report showed “no will to engage in any relevant reforms” that would protect the Swiss economy and taxpayers, but enable UBS to “catch up to global players and U.S. valuations.”

“The track record of the policymakers in Switzerland is that we had three global systemically relevant banks, and we have now one left, and these cases were the direct result of insufficient regulation and the enforcement of the regulation,” he said.

“FINMA had all the legal backdrop, the instruments in place to address the situation but they didn’t apply it — that’s the point — and now we talk about fines, and that sounds like pennywise and pound foolish to me.”

Credit: Source link